10/07/2015

Explore 'Violins of Hope' Through Dance

- Share This Story

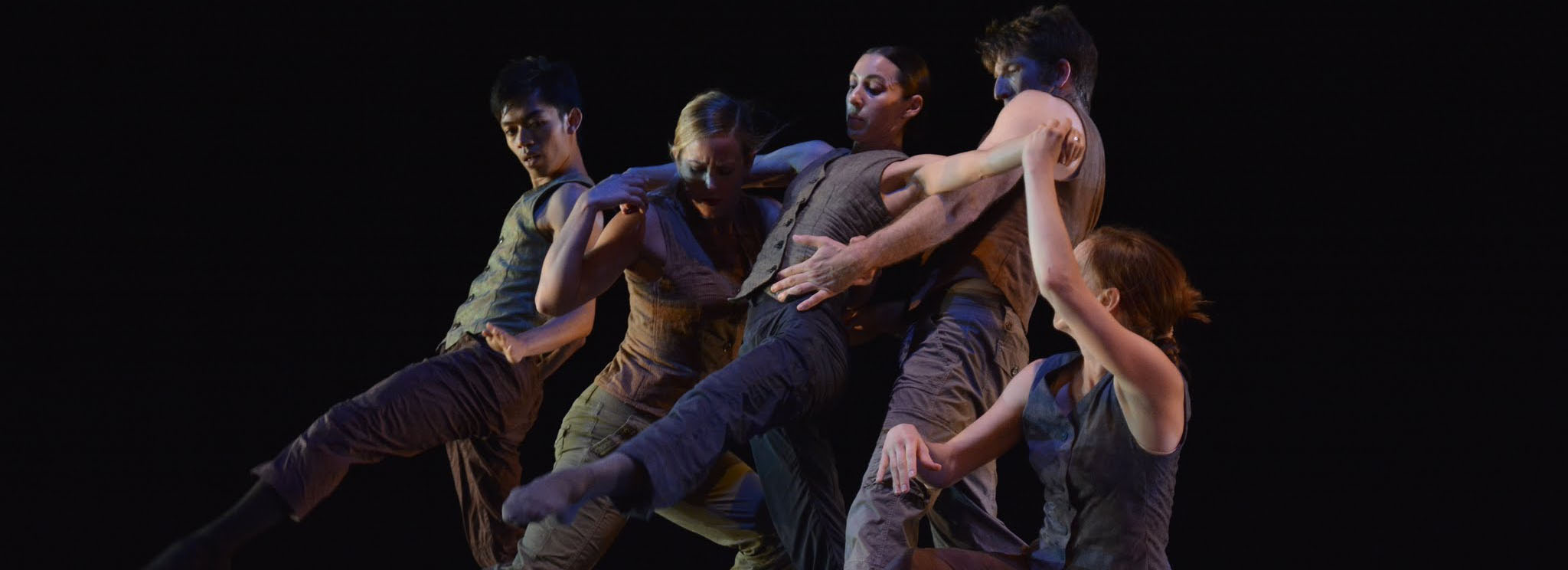

Uncovered and Elevated | Violins of Hope Collaboration To Debut October 16th

Article reprinted with permission from shark&minnow, GroundWorks DanceTheater

By Beth Rutkowski

On October 16th and 17th we will be debuting our Fall Series! As part of this series we will perform an original piece inspired by the exhibit,Violins of Hope. These violins survived the Holocaust and represent the never-ending hope of the Jewish people and their culture during that time as well as in the present day. The world-premiere work will feature an original score by renowned Israeli composer Oded Zehavi, Schusterman Visiting Israeli Artist (Israeli Institute) at Cleveland Institute of Music. Commissioned by the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage and the Jewish Federation of Cleveland’s Cleveland Israel Arts Connection, this new work is part of the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage’sViolins of Hope exhibit, which opened on October 3rd, 2015.

We recently sat down with Zehavi as well as our own David Shimotakahara to talk about the collaboration. Zehavi’s cool, intelligent, quick-witted nature pairs well with his great sense of humor – which he naturally joked about: “I always seem to be exploring dramatic themes in my work. Maybe one day I’ll create a comedy – for fun!”

His joy is infectious and his curiosity about the world clearly shapes his work. When we asked what, artistically, inspires him he had a lot to say around the feel of artistic work.

“I want art to make me feel something new – something I haven’t felt before. That’s partly what I love about David’s work. There is something very human about it – the way he puts the human body into use. It’s very fresh. It seems to create a dialogue with the audience.”

The dialogue that David Shimotakahara is creating with the audience through this particular piece stems from his original discussions with community partners at the onset of the planning process: “When Jeffery Allen at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage approached me with the idea of creating a work for the Violins of Hope Project, it was difficult to know where to begin. I was not under any mandate to create a piece specifically about the Holocaust but I wanted to make something that would honor the spirit of the Violins of Hope.“

Given the exhibit’s inherently musical nature, Shimotakahara began his creative process by thinking about the role the actual violins should play: “I assumed that the music should involve violins but how many, a string quartet or other ensemble? In thinking about scaling an idea in response to the enormity of the topic, the concept of working with only one violin seemed like it could be quite poignant.” This approach allowed the music and dance to evolve together in a cohesive way.

Zehavi remarked on the way the work plays with the music and explores physicality: “There is a moment in the piece where one of the dancers is tracing a human figure in the air. Without objectifying or being vulgar, David has a way of creating moments of appreciation and sensuality.”

The work also has a very intimate feeling, as a result of the staging, according to Shimotakahara: “Oded and I agreed on the working title ‘Shadowbox.’ I wanted all the action to feel like it takes place in a contained space. Within that, I have attempted to create a very convincing world of experience, a kind of microcosm, a keepsake of human memories and emotions. Like a child’s world our connections can be both fleeting and fragile.”

This is an extremely personal project for Zehavi. He discussed how, as an Israeli, he is very interested in the lives of Holocaust survivors – personal narratives that the piece explores in depth. “Many of my country’s founders were refugees that went through major trauma and had lost faith in mankind. They formed the country together and found a way to continue living after their traumatic experiences.”

“[The piece is] about the business of living. [Holocaust] survivors, on the surface, live seemingly normal lives. They look like everyone else but they are not. I’ve heard stories from children of survivors about their mothers hiding bread under their beds in case the Nazis come.”

Ironically, Shimotakahara began choreographing this piece through vibrant, youthful movement games: “In rehearsal I began playing with the idea of children’s games as a starting point to initiate interactions,” he says. “We worked with movement based on games like cats cradle, hand games, snakes and ladders, tag or red rover. I liked the idea that games have rules and consequences that are unpredictable. There are often elements of chance and outcomes that are arbitrary. There are winners and losers. I imagined situations where children might make up their own games. I remember as a child playing with shadows and trying capture or trace their outlines. For me this had creative implications, a kind of conjuring of memories and a desire to connect with something intangible.“

Survivors’ memories embody horrific realities that instill fear into the heart of any parent, any person. The exhibit as well as the work aims to focus on the hope that these brave individuals were able to find – the strength to keep on living after losing so much. Zehavi himself is inspired by the way that modern audiences of all faiths still find interest in this subject – perhaps as a way to explore their own identity.

Zehavi is also interested in the development of evil. “As I’ve been composing I’ve thought a lot about this poem – Hitler’s First Photograph by Wislawa Szymborska – which explores the idea of tyranny. Where it comes from, what will trigger it. It’s an incredible piece.”

Of the collaboration with GroundWorks, Zehavi says that it has been exciting: “Collaborations with choreographers take on different dynamics. Often I’m told, ‘Make [the music] sadder, happier, warmer, cooler.’ With David it’s much deeper. He uses a lot of images and provides collaborators with freedom to explore.”

It’s clear that, as a collaborative artist, he feels a strong responsibility to his collaborators and to the work. “Good music cannot save bad dance,” he states, “but bad music can ruin good dance.”

“My work with Oded Zehavi has been full of joy,” says Shimotakahara. “He delights in his own irreverence and doesn’t take anything too seriously. He is never precious about choices and loves to solve problems.”

Be sure to get your tickets for our October performances at the Allen Theater in Cleveland as well as the Akron-Summit Public Library in November to be among the first to experience this meaningful new work!

Comments